In dieser Lektion

Lesen

Am Sonntag einkaufen?

Es ist Sonntag und die meisten Geschäfte und Supermärkte sind geschlossen. Was machen diese Personen?

Adan: Ich mag österreichischen Wein, vor allem Rotwein wie zum Beispiel Blauer Zweigelt. Meine Freunde und ich mögen trockene Weine. Weißwein mag ich auch, aber nicht so sehr wie Rotwein. Ich will Wein kaufen, aber mein Weinladen ist heute geschlossen.

Lea: Heute Abend wollen meine Freunde Dragan und Nastasja bei mir essen. Dragan isst alles, aber er mag keine Paradeiser. Ich will also einen Kartoffelauflauf mit Melanzani kochen. Nastasja und ich mögen Kuchen als Nachtisch. Es ist Sonntag, aber ich muss einkaufen. Ich will heute zum Supermarkt am Bahnhof gehen.

Fatma: Schokolade mag ich am liebsten! Heute will ich in ein Cafe gehen. Dort will ich schwarzen Kaffee und einen Schokoladenkuchen bestellen. Ich darf keinen Alkohol trinken, also muss ich immer Schokolade suchen, die keinen Likör enthält.

Jakob: Ich esse nur bio, und die Biomärkte sind heute geschlossen! Samstags mag ich lange schlafen und gehe selten zum Samstagsmarkt. Jetzt habe ich Hunger und will essen. Aber es ist Sonntag– was kann ich machen? Ich frage Adan, wohin ich gehen soll.

Arbeit mit dem Lesen

Kultur

Supermärkte und Öffnungszeiten

Austria has legally regulated store opening hours (Öffnungszeiten): Monday through Friday from 5am to 9pm and Saturday from 5am to 6pm. The actual opening hours of Austrian stores vary significantly depending on the type of store. Most grocery stores are open from about 7:40 or 8am to 7:30 or 8pm. However, there are some special regulations, which typically apply to stores in towns and cities that are highly frequented by tourists. For example, a store in a major transportation centers like in a train station (am Bahnhof) or in an airport (am Flughafen) are allowed to open on Sundays and can have extended business hours until 11pm. If you need to buy groceries on a Sunday, inquire about the nearest Supermarkt an einem Bahnhof or an einem Flughafen.

In Germany, the laws governing opening times tend to be more relaxed. It is, however, still uncommon to find a grocery store there that is open on Sunday (other than at a train station or airport). In many cities, you can find a Spätkauf (“Späti” for short), a convenience store that stays open late into the night and through the weekend. There you can purchase basic grocery and household items.

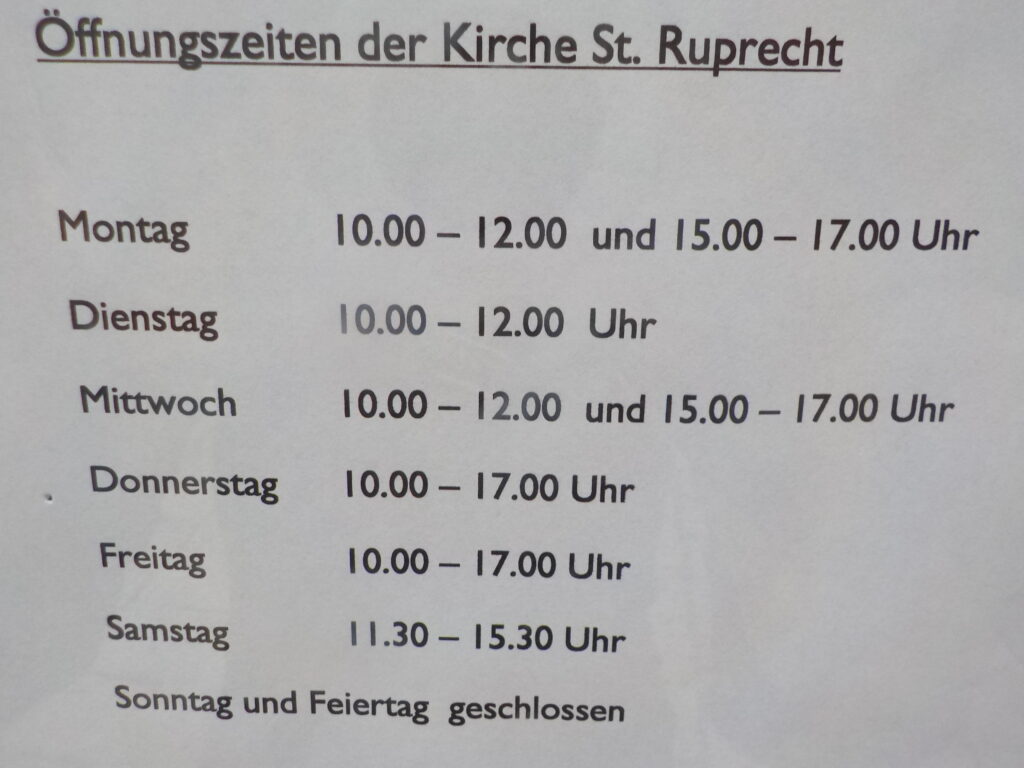

Closing on Sundays and holidays (Feiertage) is very common for shops as well as other cultural institutions. As the illustration below shows, sometimes even churches (Kirchen), are closed on Sundays!

Die 24-Stunden-Uhr

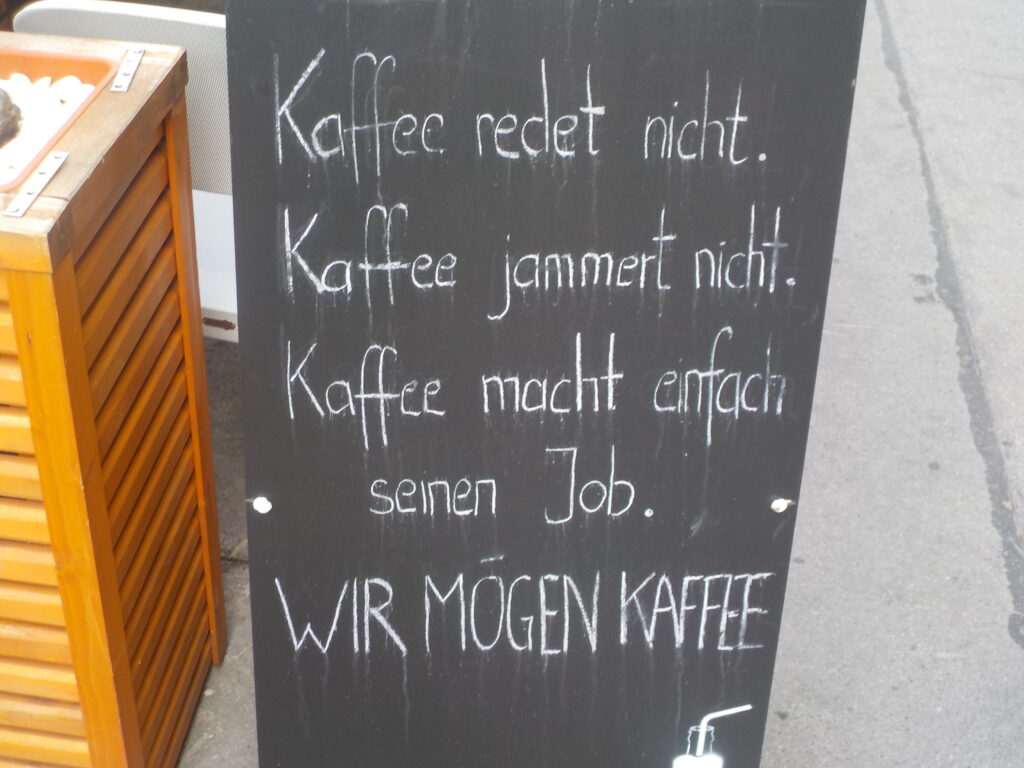

The above pictures provide examples of how German speakers tell time: they use a period rather than a colon between the hours and the minutes, and they use the 24-hour clock.

Using the 24-hour clock—sometimes called “military time” in the United States—avoids confusion between the a.m. and p.m. hours: instead of saying “5 Uhr nachmittags” (5:00p.m., or 5:00 in the afternoon), for instance, German speakers specify “17 Uhr”. To use the 24-hour clock, simply add 12 hours to any time after 12:59pm: 1.00 in the afternoon therefore becomes 13.00, while 10.00 at night is 22.00. The clock resets to zero at midnight, and midnight can be expressed in one of two ways: “0 Uhr” or “24 Uhr.” This practice thereby eliminates the need to specify “a.m.” or “p.m.” when giving times.

Strukturen

Modalverben: mögen & wollen

The above readings featuring Adan, Lea, Fatma, and Jakob’s shopping and eating habits contains a number of verbs called modal verbs. These verbs are often used in combination with other verbs and express modalities of those verbs. There are six modal verbs: mögen (to like to), wollen (to want or intend to), können (can; to be able to), müssen (must; to have to), sollen (ought to), and dürfen (to be permitted to). Over the course of this unit, you will learn to use all six of these verbs. We will begin with the first two, mögen and wollen.

Here are examples of those two verbs from the readings above:

mögen (to like)

Adan: Meine Freunde und ich mögen trockene Weine.

Fatma: Schokolade mag ich am liebsten!

wollen (to want, strongly desire, or intend to do)

Lea: Ich will heute zum Supermarkt am Bahnhof gehen.

Lea: Heute Abend wollen meine Freunde Dragan und Nastasja bei mir essen.

What the modal verbs have in common is their unusual conjugation patterns. As you can see in the chart below, mögen and wollen both show vowel changes in the singular ich, du, and sie / es / er forms: the ö in mögen becomes an a, while the o in wollen becomes an i. Additionally, the first-person singular ich and third-person singular sie / es / er / xier forms have no verb endings. These patterns are characteristic for the modal verbs as a group.

| singular | mögen (to like) | wollen (to want) | plural | mögen (to like) | wollen (to want) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ich | mag | will | wir | mögen | wollen |

| du | magst | willst | ihr | mögt | wollt |

| Sie | mögen | wollen | Sie | mögen | wollen |

| sie / es / er xier / they | mag | will | sie | mögen | wollen |

mögen

In the picture above, mögen is used to express “to like.” The last sentence on the chalkboard pictured above simply conveys that the writers like coffee. Here, mögen functions as a transitive verb (see the section on “Verbklammer” below), followed by a direct object:

Ich mag österreichischen Wein.

Natasja und ich mögen Kuchen als Nachtisch.

It can also be combined with another verb to express enjoyment of that activity:

Samstags mag ich lange schlafen.

Magst du Tofu essen?

Mögen is frequently used to express a wish or request. For this purpose, it is typically used in its subjunctive II form “möchte/n,” which means “would like”:

Heute Abend möchten wir ins Restaurant gehen.

Sabine möchte eine vegetarische Pizza.

The above examples convey a desire for a different situation than the reality: we would like to go to a restaurant (but are not currently doing so); Sabine would like a vegetarian pizza (but doesn’t have one).

wollen

Typically, wollen is used to talk about intention and means “to want to” in the sense of having a strong desire or intention to do something. Like mögen, it can appear on its own with a direct object or be combined with another verb:

Die Kinder wollen Schokolade.

Susanne will nach Österreich fahren. In Wien will sie Tafelspitz essen.

Arbeit mit der Struktur

Sprechen Sie mit einer/m Partner*in und stellen Sie die folgenden Fragen:

- Magst du kochen?

- Magst du Wurst oder Käse lieber?

- Welches Gemüse magst du?

- Welches Obst magst du?

- Willst du dieses Wochenende einkaufen? (Wenn ja: was willst du einkaufen?)

- Willst du heute vegetarisch kochen?

- Was möchtest du im japanischen Restaurant essen?

- Willst du morgen ins Restaurant gehen oder willst du zu Hause bleiben?

Strukturen

Wortstellung

Wortstellung in Hauptsätzen

A main clause, also known as independent clause, typically contains a subject and a predicate. It can form a complete sentence that is able to stand alone.

The finite verb is the one that gets conjugated to agree with the subject, as well as to reflect voice, mood, and tense.

Ich kaufe den Pullover.

Er isst das Brot.

In a German declarative sentence, the finite verb always stands in the second position, while other elements can be moved around to indicate emphases in meaning. The following sentences have the same meaning, despite the different word order:

Peter trägt den Hut. — und — Den Hut trägt Peter.

Note that in the first example, the subject (“Peter”) is in the first position. In the second example, the accusative (“den Hut”) occupies the first position, and the subject (“Peter”) is third. In both instances, the finite verb (“trägt”) is in the second position. The sentences have the same meaning, because the masculine accusative noun “den Hut” indicates that it is the direct object.

Similarly, the following two sentences have the same meaning:

Ich kaufe den Pullover. — und — Den Pullover kaufe ich.

Above, the verb “kaufe” is conjugated for the subject “ich” in both sentences, even if “ich” follows the verb in the second one.

Other parts of speech, such as adverbs of time and prepositional phrases, can precede the verb, but the conjugated verb in the main clause has to be in second position. If the subject does not precede the verb, it usually follows the verb immediately:

Heute koche ich eine Gemüsesuppe.

Am Samstag gehen Vladimir und ich zum Markt.

In diesem Restaurant arbeitet mein Freund Josie als Koch.

This allows German speakers to “front” important information– that is, to place it at the beginning of the sentence– while at the same time maintaining grammatically correct word order with the verb in second position.

Arbeit mit der Struktur

Wortstellung mit Modalverben: Verbklammer

With the exception of “mögen”, the modals generally combine with an infinitive at the end of the sentence (without “zu”). This particular structure of having a modal verb in second position and the main verb at the end of the sentence is called “Verbklammer” (verb bracket).

Sie will die Blumen kaufen.

Hans und Susi wollen keinen Brokkoli essen.

Sie mag den Käse.

Ich mag kein Fleisch. Ich bin Vegetarierin.

No matter how much information is added to the sentence, the infinitive verb comes at the end of the clause:

Am Samstag wollen wir einkaufen.

Am Samstag wollen wir auf dem Markt einkaufen.

Am Samstag wollen wir mit Olina und Janus auf dem Markt einkaufen.

Am Samstag wollen wir mit Olina und Janus auf dem Markt Käse, Obst und Gemüse einkaufen.

Arbeit mit der Struktur

Schreiben Sie eine Antwort auf die Frage, “Was wollen Sie am Wochenende machen?” Benutzen Sie mindestens 5 Verben. Besprechen Sie dann Ihre Antworten mit Ihren Mitstudenten.

Write an answer to the above question, “Was wollen Sie am Wochenende machen?“, and use at least 5 verbs. Then discuss your answers with other students.

zum Beispiel: Dieses Wochenende will ich meine Eltern sehen. Wir wollen zusammen kochen und essen….

Kultur

Sackerl und Tüten

While most grocery stores offer shopping bags to their customers, they need to be purchased. Often there is the option of paper bags with a handle (“Papiertüten”) as opposed to plastic bags (“Plastiktüten”). A selection is often located close to the registers under the conveyor belts.

Many Austrians and Germans bring their own “Stoffsackerl,” a reusable grocery bag, as they are called in Austria to the stores or the market or buy bags and then reuse them. In Germany, they are called “Einkaufstaschen.”

Unlike in Canada, many grocery stores in the US bag the purchased items for the customers. Similarly, Austrian and German grocery stores require the customers to bag their food and drinks themselves.

Increasingly more people pay with credit card (“Kreditkarte”) in stores, but the majority still uses debit cards or they pay cash (“bar zahlen”). When people have cash (“Bargeld“), many attempt to give the cashier exact change. They indicate this to the cashier by saying: “Ich habe es genau.”

Der Euro

Above are the different coins and bill available up to 20 Euros (there are larger bills available too: 50 and 100 Euro bills, for instance). What differences do you see between the denominations of bills and coins in your home country and the ones available in the Euro zone?