In dieser Lektion

Sprechen

Partner Diskussion

Diskutieren Sie zu zweit: Möchten Sie im Ausland studieren? Warum?

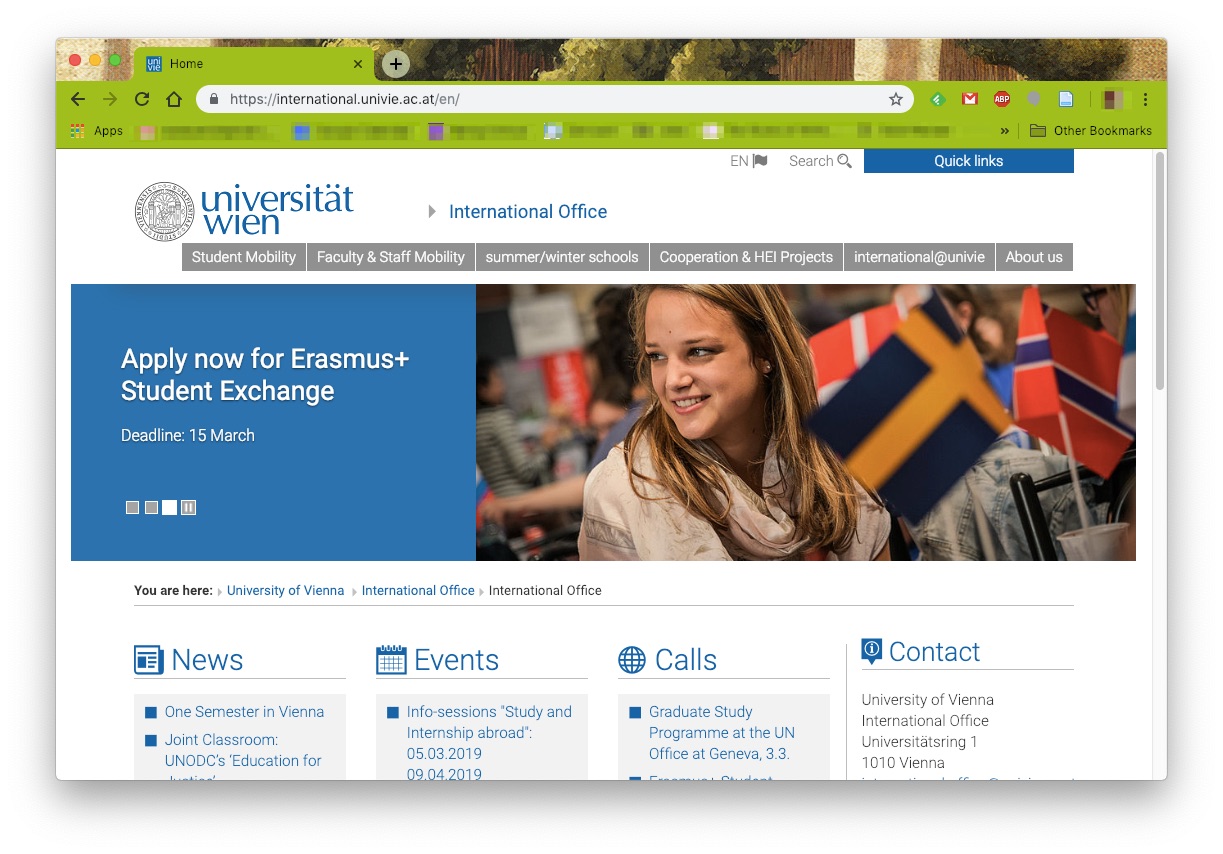

Internet-Suche

Gibt es Austauschprogramme oder Möglichkeiten für ein Auslandsstudium an Ihrer Universität?

Arbeiten Sie zu zweit und finden Sie die Webseite für das Auslandsamt an Ihrer Uni. Sammeln Sie die Informationen für ein Austauschstudium in DACHL-Ländern.

Arbeiten Sie zu zweit und finden Sie die Webseite für das Auslandsamt an Ihrer Uni. Sammeln Sie die Informationen für ein Austauschstudium in DACHL-Ländern.

| Wo? | Wann? | Wie viel Deutsch braucht man? | Weitere Informationen? |

|---|---|---|---|

Partner Diskussion (2)

Diskutieren Sie die Informationen zu zweit.

- Wo möchten Sie studieren?

- Warum?

- Was müssen Sie machen, um im Ausland zu studieren?

Hören

Vor dem Hören

Welche Vorurteile haben Sie über Deutschland, Österreich, oder die Schweiz? Womit werden Sie wahrscheinlich Schwierigkeiten haben, wenn Sie im Ausland studieren?

What assumptions do you have about Germany, Austria, or Switzerland? What do you think you will have problems with when studying abroad?

Wortschatz

Hören: Kulturschock

Arbeit mit dem Hören

Diskussion

Was denken Sie? Wie reagieren Sie auf fremde Leute? Sind Sie freundlich und offen oder zurückhaltend und ruhig? Was ist “normal” in Ihrem Land? Sammeln Sie zu zweit oder in Gruppen Ideen.

Kultur

You may have noticed Manuela saying “a bissl” a few times, a common phrase in Viennese German. In standard High German (Hochdeutsch), this means “ein bisschen” (a little). Similar to the linguistic differences between, for example, American English and British English, Austrian German has many unique words and expressions that differ from High German.

For example, all calendars begin with “Jänner” in Austria; in Germany it is “Januar.” Coffee is served with “Obers” in Austria, in Germany it is “Sahne.” You would say “das geht sich schon aus” in Austria to indicate that something will be straightened out or taken care of; if you use that phrase in Germany, it might not be understood. “Leiwand” is the Viennese equivalent of “großartig” or “toll.” And if you go to the store, be prepared to put your groceries in a “Sackerl,” not a “Tüte” like in Germany.

It should be noted, however, that some German dialects from southern Germany, especially Bavaria, overlap some with Austrian German. And within Austria, there are many different dialect regions; for example, the Alemannic dialect spoken in Vorarlberg is strongly influenced by the surrounding Switzerland and Liechtenstein.

Lesen

Vor dem Lesen

Wie kann man mit Freunden und Familie kommunizieren, wenn man im Ausland ist? Welche Mittel würden Sie benutzen? Welche nicht?

Warum möchten Sie diese Kommunikationsmittel (nicht) benutzen?

Lesen

Als Studierende ging Joan vor vielen Jahren für ein Austauschsemester nach Wien. Damals gab es kein Internet und sie schrieb ihren Freunden und ihrer Familie Briefe und Postkarten. Lesen Sie ihren Brief und ergänzen Sie die Aktivitäten dazu.

Lieber Jonas,

Grüße aus Wien!! Es freute mich zu hören, dass es Dir gut geht und dass Du gesund und glücklich bist. Mir geht es ganz gut an der Uni in Wien. Vor meinem Austauschjahr hatte ich keine Ahnung von Wien aber jetzt will ich für immer hier bleiben.

Ich traf letzte Woche einen jungen Mann an der Uni. Ich war in einem Übungssaal beim Geigen. Ich verlor mich in der Musik und bemerkte nicht, dass jemand zuhörte. Er stand draußen und wartete auf mich. Er beglückwünschte mich zu meinem Spiel und lud mich auf einen Kaffee ein. Wir tranken einen Kaffee zusammen, sprachen über klassische Musik und machten Pläne für das Wochenende.

Am Wochenende gingen wir ins Konzert. Es gab ein Konzert von dem Kammerorchester Basel im Konzerthaus. Wir bekamen Restkarten für nur 12 €. Man kann ab dreißig Minuten vor dem Veranstaltungsbeginn Restkarten kaufen. Es gab sogar zwei Sitze nebeneinander!! Danach spazierten wir durch den Stadtpark.

Ich kann nicht glauben, dass ich nächsten Monat wieder zu Hause bin. Ich mache schon Pläne, nach Österreich zurückzukehren. Es gibt eine tolle Universität für Musik und viele bekommen nach dem Studium einen Platz in einem Sinfonieorchester.

Liebe Grüße

Joan

Arbeit mit dem Lesen

Kultur

You’ve read and written letters in German before, but let’s take a closer look at Joan’s letter to review the format. Then in the Erweiterung to this lesson, you’ll be writing your own letter.

- What greeting does Joan use? What punctuation after the greeting?

- What do you notice about the capitalization in the letter?

- What closing does Joan use? What punctuation after the closing?

Just like in English, personal letters frequently start with “Dear [Name]”—in this case Lieber Jonas—followed by a comma. But here is another moment where the gendered nature of the German language rears its head: the ending of the adjective lieb has to match the gender of the person to whom you are writing, so you would have Liebe Joan (for a female-identified person) but Lieber Jonas (for a male-identified person). (You will learn more about adjective endings in the following lessons of this unit.) What do you do if you don’t know the pronouns of the person to whom you are writing? Excellent question with no real solution. The only answer is to try to avoid the “Dear SoAndSo” form of address in a situation like that. This could be done by saying “Hallo” in combination with the first name or, in more formal situations, starting the letter with “Guten Tag,” with or without the full name of a person.

Note that there is a comma after the salutation of a letter, unlike after the closing, where there is no comma before the name. Here Joan uses Liebe Grüße which is an informal closing, akin to “Love, Joan.” Another common closing for a letter is Mit freundlichen Grüßen which is sometimes abbreviated as MfG, particularly in email.

And what’s up with the capitalization of Du? In letter writing, capitalizing all forms of du and dein is a form of respect to the addressee. Think of it as a comparison to the capitalization of Sie for the formal form. This convention is still used, but not always these days.

One other convention to note is that the first word of a letter is only capitalized if it is a noun. Joan starts her letter here with “Grüße aus Wien!” It’s capitalized because Grüße is a noun. If she had started with a preposition instead, for example, she would not have capitalized the first word: “seit acht Monaten studiere ich als Austauschstudentin in Wien.”

For more information about the conventions of writing a letter, do some googling: go to google.de and try using the question “wie schreibe ich einen Brief?” and see what advice you can find. What additional forms of address (die Anrede) can you discover? What other closings (der Briefschluss)? Are there other important elements to a letter that you don’t see in this example? What are some of the differences between an informal letter like this and a more formal letter?

For more information about the conventions of writing a letter, do some googling: go to google.de and try using the question “wie schreibe ich einen Brief?” and see what advice you can find. What additional forms of address (die Anrede) can you discover? What other closings (der Briefschluss)? Are there other important elements to a letter that you don’t see in this example? What are some of the differences between an informal letter like this and a more formal letter?

Strukturen

Imperfekt – unregelmäßige Verben

So far you’ve learned about the Imperfekt with modal verbs and weak, regular, and rule-following verbs. In this section we’ll cover the irregular, strong, non-rule-following, and different-rule-following verbs. (That seems like a lot, but it’s not so bad.) If you encounter a verb that was “irregular” in either present tense or Perfekt, it will be “irregular” here too.

Let’s look at these exceptions one at a time.

Starke Verben

First we have strong verbs. As you learned, there are strong and weak verbs. We have encountered these in the present tense and with the Perfekt. The weak verbs follow the rules, but the strong verbs fight against the rules – even though they have their own rules. Here are the rules for the strong verbs.

- change the vowel (or in some cases the consonant)

- add the strong verb ending

You will note that this is very similar to what we do with modal verbs as well, but the endings are different. Some examples include fahren, lesen, and gehen. Take a look at the chart below to see how this works.

| Endung | fahren | lesen | gehen | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | ||||

| ich | – | fuhr | las | ging |

| du | -st | fuhrst | las(e)st last | gingst |

| Sie | -en | fuhren | lasen | gingen |

| sie / es / er / xier | – | fuhr | las | ging |

| Plural | ||||

| wir | -en | fuhren | lasen | gingen |

| ihr | -t | fuhrt | last | gingt |

| Sie | -en | fuhren | lasen | gingen |

| sie | -en | fuhren | lasen | gingen |

As you can see, the endings on these are different than on weak verbs, but they still follow a pattern/rule. Note the vowel changes. There are general guidelines to figure out how the vowels will change, but for the most part you just have to memorize it. (I know that’s not what you wanted to hear.)

**Achtung – Call back to previous grammar**

Remember when we learned about strong verbs in the present tense? The Verbs fahren and lesen both had vowel changes in the present tense for “du” and “sie / es / er / xier” forms, so we already think of them as strong verbs. If you can remember this, it is a clue that they will have a vowel change here too – just a different vowel change. Of course that doesn’t explain gehen, right? Remember, some things you just have to memorize.

Let’s practice this a bit with some verbs that you know.